The Passion According to G.H.

In my fresh, damp, and cozy home.

The Passion According to G.H.

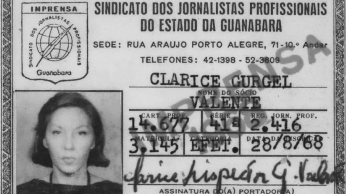

Let me clarify this matter once and for all: I am sorry to have to tell you that there are no mysteries and these myths are untrue. My story is as follows: I was born in the Ukraine, the homeland of my parents. I was born in a village called Tchechelnik, which is too small and insignificant to appear on any map. When my mother was expecting me, my parents were already planning to emigrate either to the United States or to Brazil. They waited on in Tchechelnik until I was born and then set out on their long journey. I was two months old when I arrived in Brazil.

“One Final Clarification,” in Selected Crônicas

In Recife there were lots of streets with large villas on either side, surrounded by extensive gardens, where rich people lived. I used to play a game with another little girl in order to decide who owned those villas. ‘That white one is mine.’ ‘No, it isn’t, we’ve already agreed the white ones are mine.’ But that one isn’t all white for the windows are green. Sometimes we would stand there for ages, our faces pressed against the railings as we peered in.

“A Hundred Year’s Pardon,” in Selected Crônicas

My father was a great believer in sea-bathing during the summer months. And how I loved those outings to the seaside at Olinda near Recife. My father also believed that the best time for sea-bathing was before sunrise. Difficult to describe my sense of wonder as we boarded an empty tram in the dark in order to reach Olinda before the sun came up.

“Sea-bathing,” in Selected Crônicas

Belém

Naples

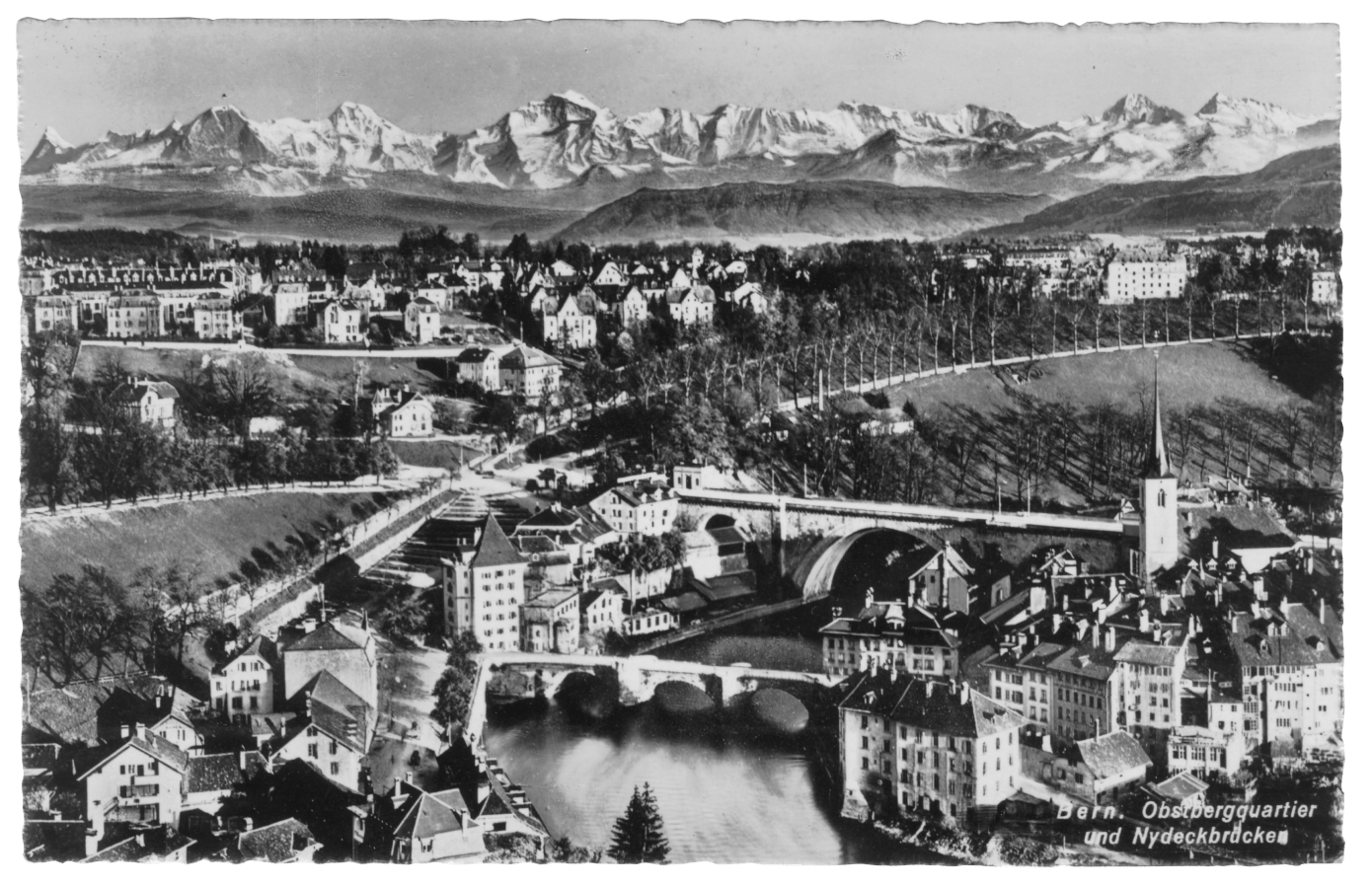

Bern

Torquay

Washington

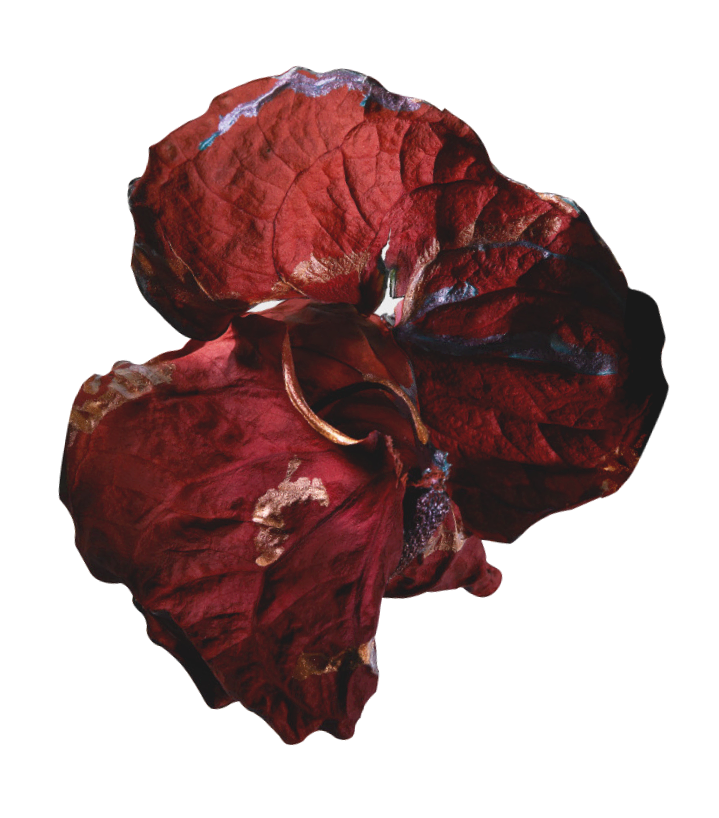

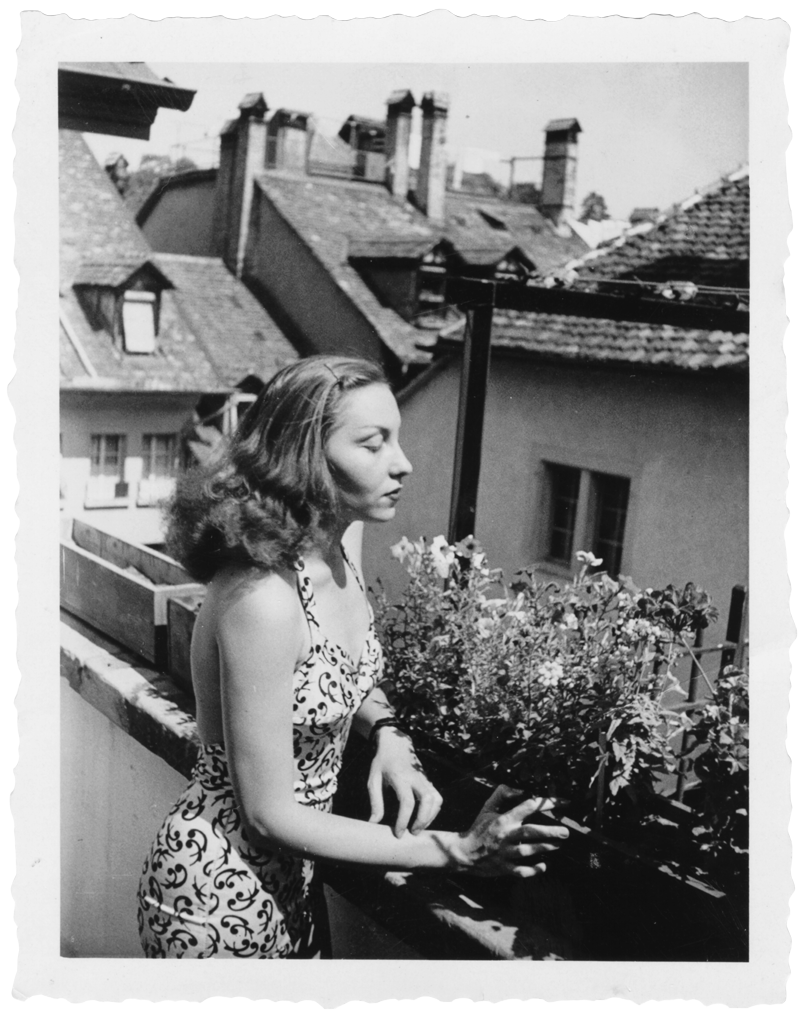

St. Moritz, 1948

It's beautiful here. It's a dirty and disorganized city, as if its main elements were the sea, the people, the things. People seem to live in a provisory manner. And everything here has faded colors, but not as if there were a veil over them: they are true colors.

It's a pity that I don't have the patience to like such a tranquil life as this in Bern. It's just like a farm.

A postcard from Bern, the city where Clarice lived with

Maury from 1946 to 1949, and where she gave birth to her first son, Pedro

For me, London was mysterious and pulsating with life, yet grey. And everything grey has a strange effect on me (…).

"London's Bridges," in Selected Crônicas

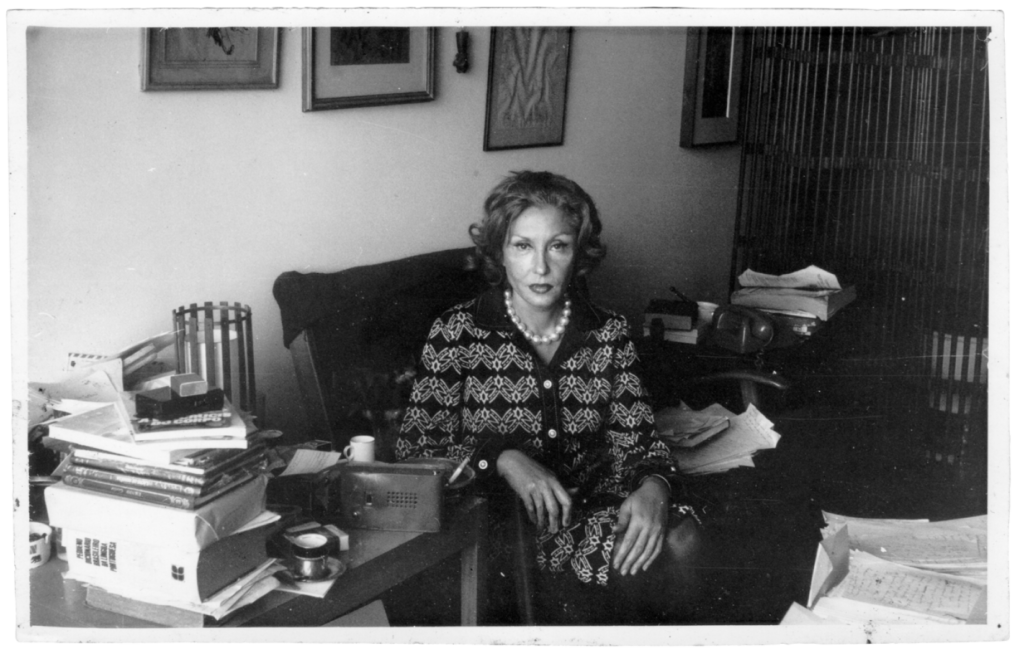

Clarice at her home in the neighborhood of Leme, Rio de Janeiro.

I remember a night in Poland, at the house of one of the embassy's secretaries, in which I went alone to the terrace: a great black forest pointed me, emotionally, in the direction of Ukraine. I felt its appeal. Russia had a claim on me, too. But I belong to Brazil.

The short story "Happy Birthday," deconstructing the question of appearances, of masks, and of the falsity inherent in social facts, orbits around a ritualized family event: the birthday celebration of one of its members. It is, in all certainty, a paradigmatic text, in the sense that, in focusing on the birthday table, it summarizes the spirit of the other short stories in the book. That is precisely why Roberto Corrêa dos Santos claims that the text delineates "the logic of the short stories in the book Family Ties. The 'ties' of the family constitute, simultaneously, proximity, distance, dilaceration, and imprisonment."

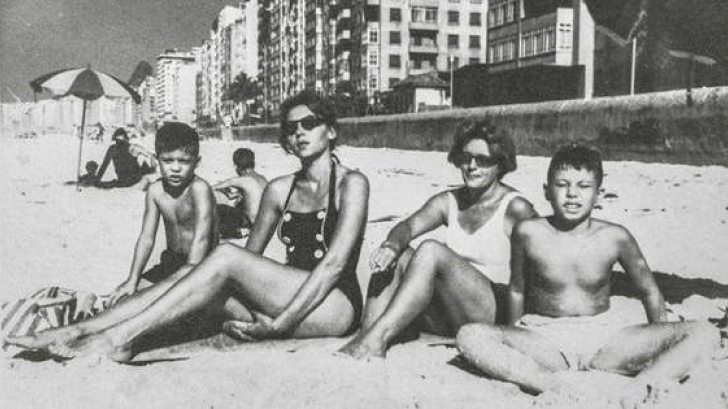

I still haven’t taken in Rio, I’m slow and difficult. I would need a few more months to understand the atmosphere again. But the fact is it’s nice. It’s wild, it’s unexpected, and run for your lives.

This morning, when dawn breaks and the sun rises, I'll go to the beach. I'll get in the water. It's so good. Ah, how many gifts! For example, that I'm still alive and can swim in the sea.

Why had I chosen the Botanical Gardens? Just to look. To see things. To feel them. Just to live. I leapt out of the taxi and went through the wide gates. Into the welcoming shade. I stood there motionless. Green life in those gardens was so abundant. I could see no meanness there: everything gave itself completely to the wind, to the atmosphere, to life, everything reached for the sky. And what is more: also surrendered its mystery.

“The Gratuitous Act,” in Selected Crônicas

The Botanical Gardens in Rio de Janeiro.

Photo by Camillo Vedani, circa 1868

I saw a thing. A real thing. It was ten o'clock at night at Tiradentes Square, and the taxi was speeding. Then I saw a street I'll never forget. I won't describe it: it's all mine. All I can say is that it was empty and it was ten o'clock at night. Nothing more. I was, however, germinated.

Água viva

The word is my fourth dimension.

Água Viva

When I learned how to read, I devoured books, and thought that they were like a tree, an animal, a thing that is born. I didn't know that there was an author behind everything. Some time later, I found out that it was so, and said: "I, too, want this for myself."

"Declarations for Posterity," interview to Museum of Image and Sound, October 20, 1976

I was a member of a public library. With no guidance, I chose the books by their titles. And so it was that, one day, I chose a book entitled Steppenwolf, by Hermann Hesse. [...] And I, who was already writing brief short stories, [...] started to write a long one attempting to emulate it: the interior voyage fascinated me. I had entered into contact with high literature.

"O primeiro livro de cada uma de minhas vidas" (The First Book of Each One of My Lives), in Todas as crônicas (All the Chronicles)

It was the Portuguese language which influenced my spiritual life and innermost thoughts, and this was the language I used to utter words of love.

“One Final Clarification,” in Selected Crônicas

I write in acrobatics and pirouettes in the air – I write because I so deeply want to speak. Though writing only gives me the full measure of silence.

Água Viva

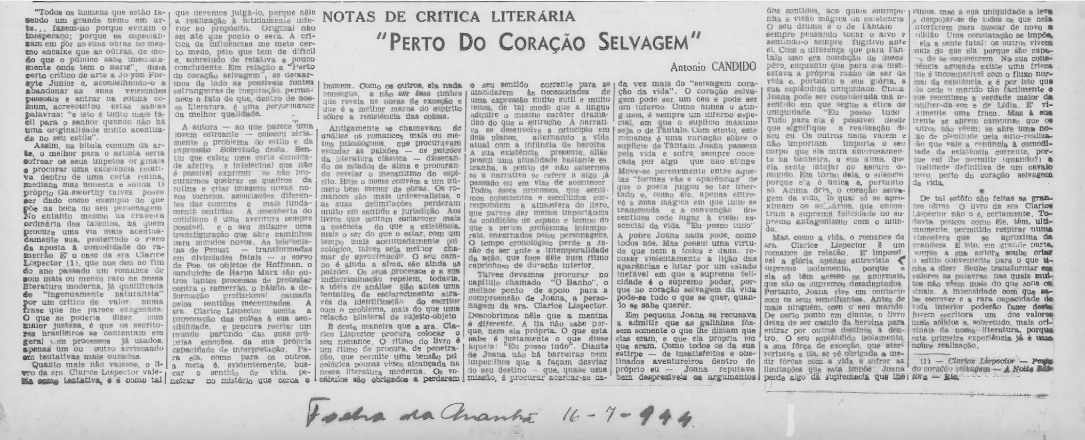

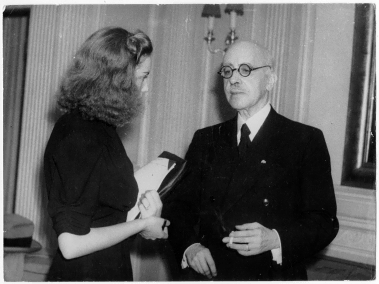

Antonio Candido's review of Perto do Coração Selvagem (Near to the Wild Heart, 1943), Clarice Lispector's first novel, published in the newspaper Folha da Manhã, July 16, 1944

Hélène Cixous, in “By the Light of an Apple”:

If Kafka had been a woman. If Rilke had been a Jewish Brazilian born in the Ukraine. If Rimbaud had been a mother, if he had reached the age of fifty. If Heidegger had been able to stop being German, if he written the Romance of the Earth. Why have I cited these names? To try to sketch out the general vicinity. Over there is where Clarice Lispector writes. There, where the most demanding works breathe, she makes her way. But then, at the point where the philosopher gets winded, she goes on, further still, further than all knowledge.

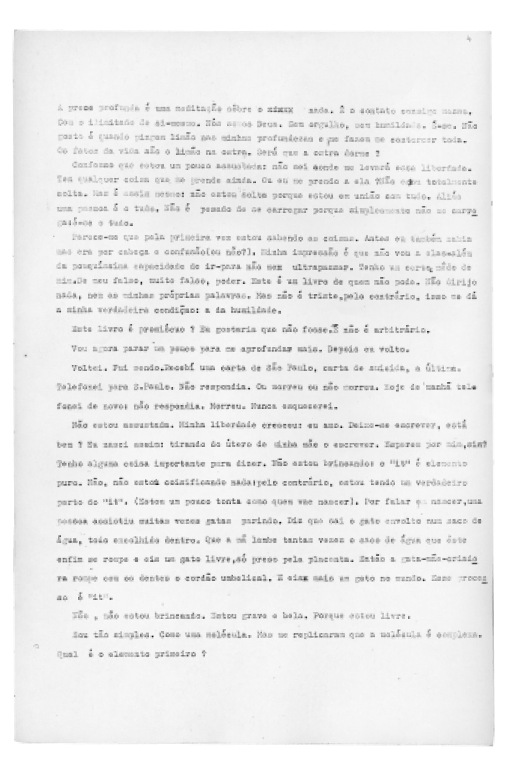

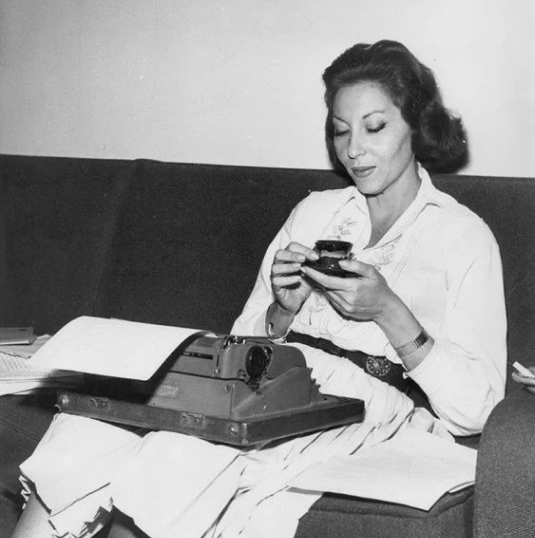

By describing herself as "anonymous and discrete" in her books, Clarice transferred to the crônica all the burden of intimacy and biographizing, as if she were impelled by an uncontrollable force. And, curiously, this force seems to come from outside of her. Not from a superior instance, mystical or divine, but from something rather prosaic: her typewriter.

In writing a weekly column I am allowing readers to know me. Am I in danger of losing my privacy? What am I to do? I type out my articles at the speed of the typewriter, and when I look to see what I have written, I realize I have revealed something about myself. I even believe that if I were to write an article about the over-production of coffee in Brazil, I should end up sounding personal. Am I in danger of becoming popular? The thought horrifies me. I must see if anything can be done to remedy the situation. Words by Fernando Pessoa which I read somewhere give me some reassurance: “To speak is the simplest way of becoming unknown.”

“Fernando Pessoa to the Rescue,” in Discovering the World

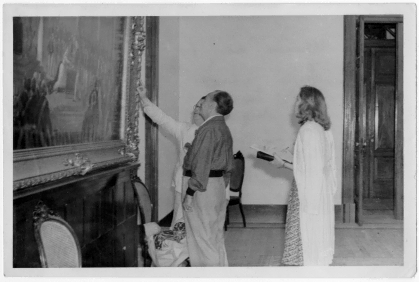

Clarice Lispector among writers and friends: Carolina Maria de Jesus; Fernando Sabino; Lauro Moreira, Marly de Oliveira, and Manuel Bandeira; Erico and Mafalda Verissimo, godparents to her sons, Pedro and Paulo; Lygia Fagundes Telles and the Argentinian writer Antonio Benedetto

I've always written for the press. In the magazine Senhor, for example. It published something of mine every month. In terms of popularity, it may have been very important. I'm bold for a shy person.

"Declarations for Posterity," an interview with the Museum of Image and Sound, October 20, 1976

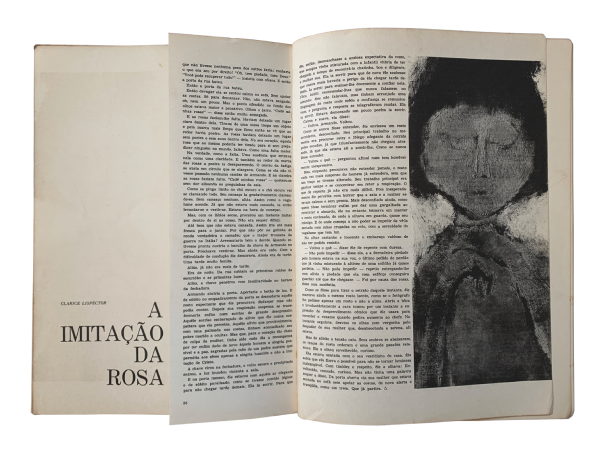

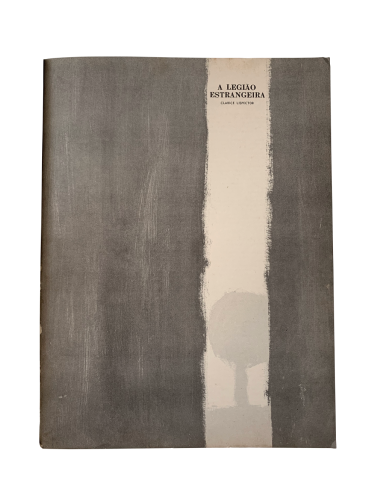

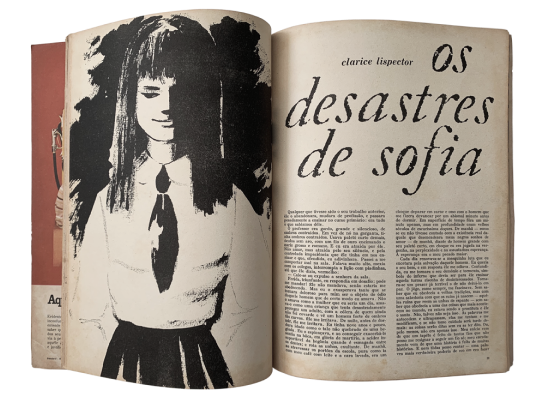

Covers of the magazine Senhor, which published Clarice Lispector's celebrated short stories in the 1950s and 1960s

[...] oftentimes my so-called intelligence is so meager that it's as if I had a blind mind. People who talk about my intelligence are actually confusing intelligence with what I shall now call intelligent sensibility. This I have, and have had many times. And, though I admire pure intelligence, I find this intelligent sensibility more important for living and for understanding others.

“Love,” in The Complete Stories

And death was not what we thought.

“Love,” in The Complete Stories

Georges Bataille, in Eroticism:

Life is always

a product of the

decomposition

of life.

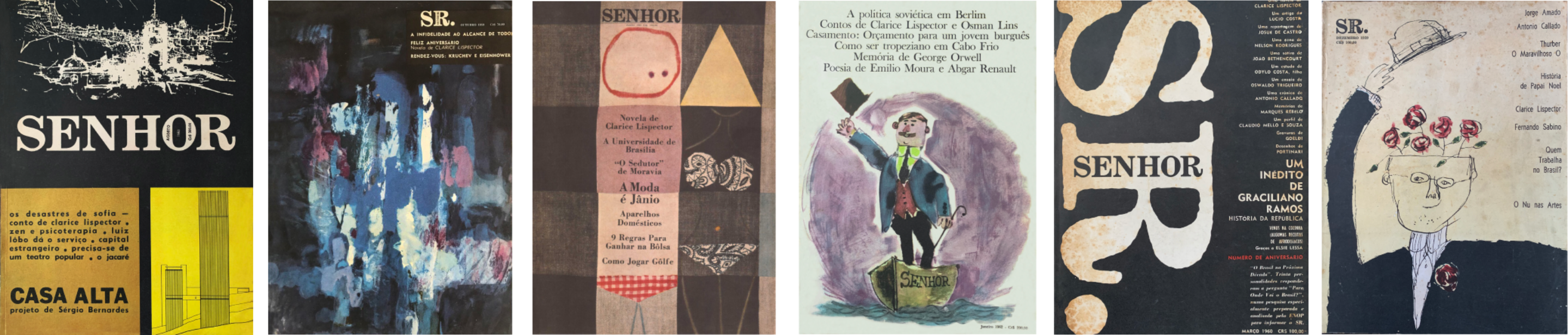

There was a secret labor underway in the Garden that she was starting to perceive. In the trees the fruits were black, sweet like honey. On the ground were dried pits full of circumvolutions, like little rotting brains. The bench was stained with purple juices. With intense gentleness the waters murmured. Clinging to the tree trunk were the luxuriant limbs of a spider. The cruelty of the world was tranquil. The murder was deep.

“Love,” in The Complete Stories

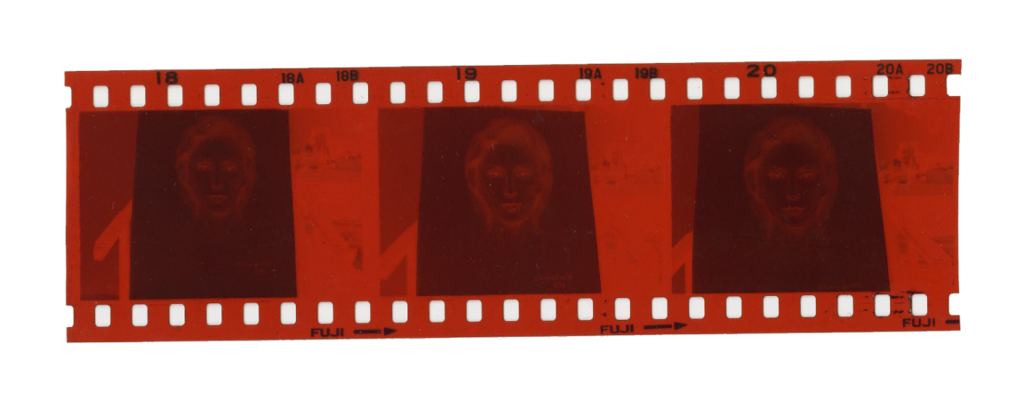

Negative film: photo of a portrait of Clarice by Dmitri Ismailovitch, 1974.

Clarice Lispector's world is scatological, sexed, rhythmed by pulsations: a nauseating world of strong, raw, rotten, and sensual scents – odors of quicklime and filth, of sea breeze, of cemeteries and things stored away, of stables, of cows, of blood, of elephants, and of sweet jasmine and of fish.

[...] Living beings are turgid and viscous things, like thick and fleshy petals, voluminous dahlias and tulips, thick stems and silent plants; useful objects are solid and impenetrable things, such as lamps and display cabinets, trinkets, and water pipes.

Fear has always guided me to the things I love; and because I love, I become afraid. It was often fear which took me by the hand and led me. Fear leads me to danger. And everything I love has an element of risk.

“Creating Brasília,” in Selected Crônicas

“Explicação de uma vez por todas”, em Todas as crônicas.

Fear. Oil on wood, by Clarice Lispector, 1975

Oh, how I long to die. As yet I do not know what it means to die – what paths are still open to me.

Springtime Racing with the Typewriter, in Discovering the World

“Explicação de uma vez por todas”, em Todas as crônicas.

Before learning how to read and write, I already fabulated. In fact, I invented with a friend a story that never ended. [...] it went like this: I started, everything was very difficult; both of them died... Then she'd come and say that they were not that dead. And it all would start over again...

“Declarations for Posterity,” interview to

Museum of Image and Sound, October 20, 1976